The Bird and the Sea Story and illustrations by Loika

The sun rose over the mountain side first in sound, then in colour: birdsong and wingbeats, a dash of rich blue, a glint of orange. The valley forest was an orchestra conducted by the morning breeze. Overhead, the stars were vanishing.

The mountain bird had always liked sunrises, and it flew in the light now, turning in the rays so that its form from a distance would have been swallowed up in the brightness. Far below, it could see a lone traveller beginning to move through the trees.

The bird was a traveller of sorts, too. It had made a promise.

It flew down now so that the traveller would see it, and say hello. The morning was cold.

“Hello!” called the traveller.

“Hello!” replied the bird, landing softly.

“Where are you headed on this lovely day?” asked the traveller.

“To the sea,” replied the bird.

“The sea!” exclaimed the traveller. “Why, just past the next valley on the other side of this mountain the winter snows have already melted, and there is laughter there to be had for all.”

“Even so,” said the bird, “I must go to the sea.”

“What is there to be had at the sea?” asked the traveller.

“Well,” said the bird, “the sea salt, for one, and the endless water, for another. It is always warm, down by the sea. And the food there is quite nice. That is what they all say.”

“I have a cousin who swore by the sea,” offered the traveller, “but I have always preferred the mountains, myself.”

“The mountains are beautiful,” agreed the bird, with an air of wistfulness.

“If we were headed the same way,” said the traveller, “we could have perhaps kept each other company. How sad to part when we have only just met.”

“Things come,” said the bird, “and things go. But go well.”

“And the same to you!” said the traveller.

The mountain bird took wing, and began to follow the river.

A child was playing by the edge of a waterfall. The river had joined many others, and now they all rushed forth in splendour. The mountain bird alighted on a fallen branch, snagged between rocks and leaping water. The afternoon was a swirling golden haze.

“Bird!” cried the child.

“Yes?” said the bird.

“Teach me to fly!”

“Impossible,” replied the bird. “You don’t have wings.”

“My mum says I can learn anything if I try,” said the child.

“Not this.”

The child frowned. “But I want to fly to all sorts of places like you.”

“You have legs.”

“Legs are boring.”

“Ah,” said the bird, who could not quite bring itself to disagree.

“Where are you from?” asked the child, after a pause.

“The mountains, some valleys behind us.”

“Where are you going?”

“The sea.”

“Oh!” exclaimed the child. “Like a lake, but bigger?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Why?” repeated the bird. “Where are you going, then?”

“I’m not going anywhere,” said the child. “Just home.”

“Yes,” sighed the bird. “Exactly.”

“Why are you going to the sea?” asked the child again, with persistence.

“Hm,” hummed the bird, looking off into the distance, “for instance, imagine that there are several pieces of you, and you only feel like yourself when those pieces are all together in the same place. But you’ve accidentally lost a piece here, or a piece there, or this other piece just sort of got up and left on its own. That’s why I’m going to the sea.”

“To get one of your pieces back? Like a quest?”

“Actually,” the bird said, “there’s no piece of mine at the sea.”

“I don’t understand.”

“That’s okay,” replied the bird. “It’s just a story.”

It was becoming quite dark.

“I have to go,” said the child, “or my mum will worry.”

“Go on, then.”

“Bye-bye!”

“Goodbye,” said the bird.

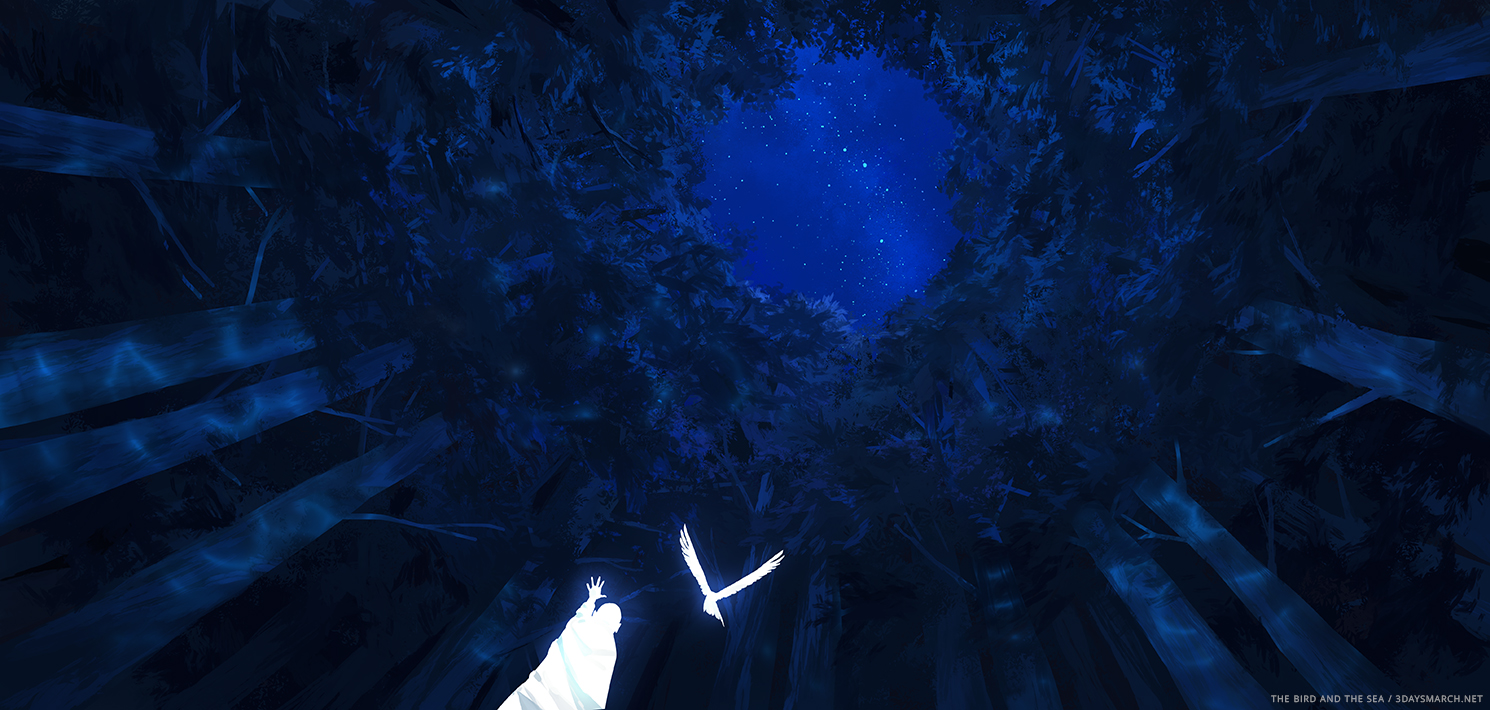

“I’m blind, you see,” explained the hermit.

There was no moon, and the surrounding forest was dark. The hermit sat on the flattened stump of what must have once been a great tree.

“This place is like being at the bottom of a well,” the hermit continued. “The canopy is so distant; everything is miles away.”

“A well?” questioned the bird.

“Yes.” The hermit coughed, and gestured with one hand, plunging it in a curve towards the ground. “In some places, if you dig deep enough you will find water. Like that.”

The mountain bird was not familiar with digging holes in the ground to look for water, for it had lived near mountain springs and rivers all its life. But it was true that the trees around them grew tall and straight, and the night was thick as though it were liquid. The bird looked up at the small patch of stars overhead and imagined being underwater. The light was where the surface was, it thought, and said so.

“That’s right,” agreed the hermit. “My eyes can still sometimes see some bright light during the day, and that is when I like to sit here most, facing upward.”

“It doesn’t frighten you?”

“No. It is very calming.”

“I think so, too.”

“Ah,” said the hermit. “But you have never been so far underwater.”

“I haven’t,” conceded the bird.

“Neither have I, to tell you the truth.” The hermit coughed again, and laughed. “That is precisely why it is so appealing. Is it not so?”

It was so—for the first time, the mountain bird felt as though some essential part of its being had been seen and understood.

It was extremely strange.

The plains were thick with tall grass and flowers of every colour. Midday warmth was in the dance of the river water, the flashing fish scales, even the shadows of the rocks.

The mountain bird was flying high in slow meandering arcs. The wind was good, and it had come so far: there was no rush.

Down below, a caravan trundled. Its horses were well fed and watered, the road was familiar. There was laughter and song, rising in the air.

“Golden river running down,” began a lilting voice, “down to an ocean of green.”

“And in the mountain hollow, still,” another continued, “swims my love unseen!”

“A beautiful wish, a forgotten child.”

“So far from the shore and its turbulent peace.”

It was much better to fly somewhere, thought the mountain bird, than it was to be enveloped always by thousands of branches repeating the same scenery day after day. Again and again and never again. It had made the right choice. The caravan was rolling along a beaten path placed there by thousands of other wheels: there was always a line from here to there that one could follow. So goes the wide-eyed child to old age, and so too goes the river to the sea.

Eventually the singing stopped, and a young voice from within the caravan began to cry.

“Shh,” said an older voice, soothing. “It’s okay.”

“It’s okay,” echoed the mountain bird, high above.

They were nearly there.

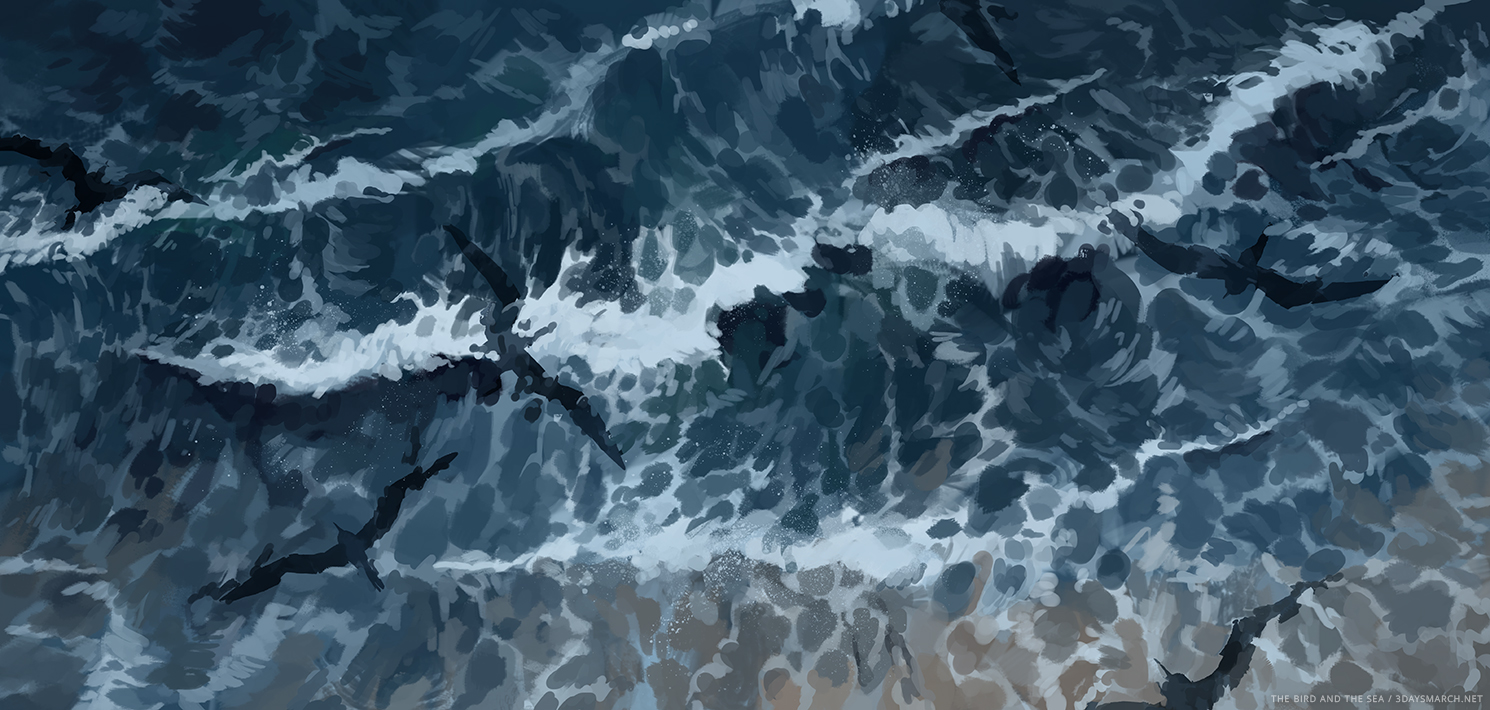

The sky was an endless grey, and the sea was its great roaring shadow.

The mountain bird came to rest on the edge of a cliff. It did not feel as though it could fly any further.

All along the cliff sea birds flocked.

“Hello,” said one.

“Who are you?” asked another.

“Why are you here?” inquired a third. “Are you lost?”

All the sea was, thought the mountain bird, was a vast body of water. It was pulled first here, then there by the moon. Its surface shifted with the wind. Inside it swam life and death and waste. It asked no questions, held no conversation. It was beautiful. In the sea, one could drown.

By the shore were two people. One had lined her pockets with stones, and the other was running along the water, kicking at the froth, laughing. They were both so incredibly far away.

An edge was very final. An edge was an invitation by gravity.

The mountain bird felt within itself a deep contentment.

It closed its eyes. It fell asleep.

Fin